Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

The Occult Harry Smith

The Magical and Alchemical Work of an Artist of the Extremes

Table of Contents

About The Book

• Explores in depth the occult and mystical side of Smith—his “heaven and earth magic”—focusing on how his varied artistic efforts were part of a comprehensive magical and alchemical practice

• Includes unpublished photos of and letters from Smith, rare interviews, one of his unpublished texts, and essays by scholars and friends

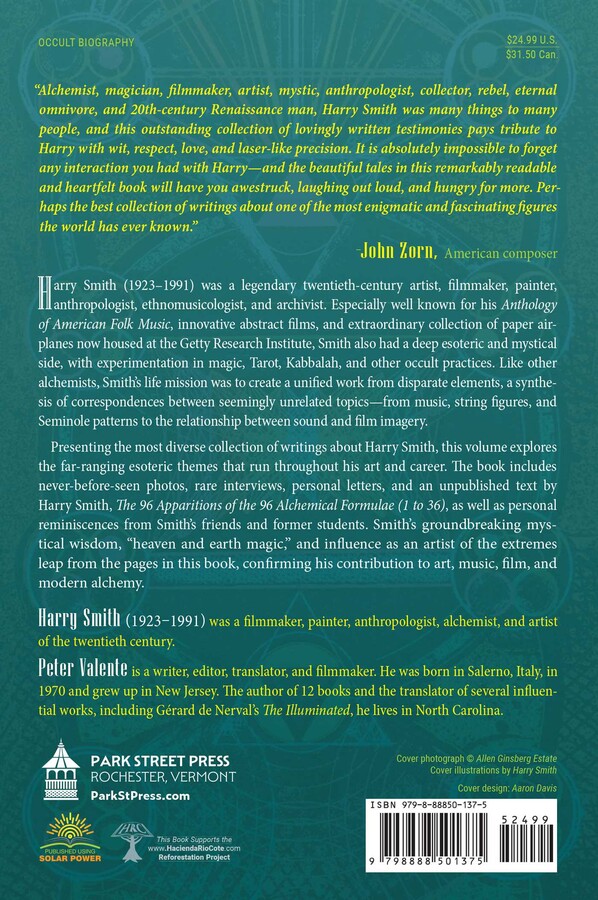

Harry Smith (1923–1991) was a legendary twentieth-century artist, filmmaker, painter, anthropologist, ethnomusicologist, and archivist. Especially well known for his Anthology of American Folk Music, innovative abstract realms, and extraordinary collection of paper airplanes now housed at the Getty Research Institute, Smith also had a deep esoteric and mystical side, with experimentation in magic, Tarot, Kabbalah, and other occult practices. Like other alchemists, Smith’s life mission was to create a unified work from disparate elements, a synthesis of correspondences between seemingly unrelated topics—from music, string figures, and Seminole patterns to the relationship between sound and film imagery.

Presenting the most diverse collection of writings about Harry Smith, this volume explores the far-ranging esoteric themes that run throughout his art and career. The book includes never-before-seen photos, rare interviews, personal letters, and an unpublished text by Harry Smith, The 96 Apparitions of the 96 Alchemical Formulae (1 to 36), as well as personal reminiscences from Smith’s friends and former students. Smith’s groundbreaking mystical wisdom, "heaven and earth magic," and influence as an artist of the extremes leap from the pages in this book, confirming his contribution to art, music, film, and modern alchemy.

Excerpt

Mystic Traveler

Thoughts on Harry Smith

Raymond Foye

There is a photograph of Harry Smith, aged nineteen, sitting in a Lummi Indian smokehouse, at the controls of an audio recorder. It is a remarkable image that freezes Smith in an idealized setting he would live his life attempting to recreate: a tribal group where every person had a valued role, living in harmony with the environment and doing no harm; a culture rich in song and dance and works of art where shared values and meanings were not divorced from everyday life; and a society that placed at its center the honored and respected figure of the shaman. It was a social model that Smith pursued throughout his life, and one that he most closely achieved in the 1960s, when the Chelsea Hotel was the tribe, and he was the shaman.

As a high school student on a weekend visit early in 1974, I met Harry at the Chelsea Hotel at a time when it had not yet taken on the expensive elan of its later years. A room could be rented for $30 per night, slightly inflated from the ten dollars a night when Harry moved in, when the hotel was listed in "New York on Twenty-Five Dollars a Day." I was sitting in the lobby late one afternoon when Harry approached me. I had seen him passing in and out of the hotel several times that day. Gnome-like, with gray-and-white ponytail and bedraggled beard, he had sensitive blue eyes that peered out from behind enormous spectacles. He wore thrift shop clothes in combinations of plaids and stripes that did not remotely match. The most distinctive feature about him was the way he smelled: a not-unpleasant mixture of tobacco, incense, marijuana, and Miller High Life beer. He ambled up to me in the lobby and struck up a friendly conversation. After several minutes he extended an invitation to visit him later, in his high nasal pitch, a slight twang to a voice that was erudite, sardonic, and inveigling by turns: "Just remember, I’m in Room 731. That’s seven planets, three alchemical principles, and one god," emphasizing the last two words by holding up a crooked index finger.

I decided to take Harry up on his invitation to visit. Fortunately, I first called up from the lobby on the house phone, as I later learned this was de rigueur, and anyone who violated this rule, even unwittingly, would find themselves the brunt of an outburst that would force one backward into the hallway. His room was like stepping into a nineteenth-century cabinet of curiosities. The most prominent feature was the enormous number of books and records, meticulously arranged on gray steel shelving, eight feet high by sixteen feet long, arranged in rows that formed narrow corridors within the room itself. The records were arranged not by subject or artist but by the label they were released on, and by numerical order of serial numbers, as Harry did not so much collect records as entire record labels. On his shelves stood the complete catalogs of Bluebird, Riverside, Vocalion, Smithsonian, UNESCO, Folkways, Das Alte Werke, and so on. Sitting there one idle afternoon I estimated there were almost thirty thousand records in this room. After smoking a joint Harry would stand with arms folded in front of the collection and sigh in his familiar whine, with mock exasperation, "There’s nothing to listen to!"

Hanging out with Harry mostly consisted of smoking pot and listening to records. In those years the records one listened to most were: 1) Kurt Weill’s and Bertolt Brecht’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (the 1956 recording with Lotte Lenya); 2) Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde (especially when psychedelics were consumed); and 3) a tie between Eskimo Songs from Alaska and Sounds of North American Frogs—both Folkways LPs. The cardinal rule in listening to records with Harry was NO TALKING: absolutely none whatsoever until the record was finished.

His books were arranged by height, a curious system of organization and one I’d never seen before. When I asked Harry about this, he explained that it took up less space, and in any case, he always remembered a book visually by its placement. One was never allowed to touch the books or records—or anything else in the room for that matter. To casually pick something up was out of the question. I would often stand in front of the shelves (and later when he trusted me more, venture down one of the tiny corridors of shelving) to peruse the spines: volumes on Theosophy, Eliphas Levi, the Elizabethan astrologer John Dee, Athanasius Kircher, alchemists Robert Fludd and Ramon Llull; a complete set of The British Journal of Psychical Research; Smithsonian journals on folklore and American Indian studies; the Oxford English Dictionary; books on linguistic theory by Ferdinand de Saussure and Roman Jakobson; expensive art books on Eskimos, Tibetan tankas, and ornithology. All were bookmarked with yellow slips of paper and extensively notated in pencil in the back. Occasionally Harry would take a book off the shelf to illustrate a point, and there was never a reference in any of the thousands of books that Harry could not explain in relation to numerous other subjects. In one of my notebooks of the time I have a quote from Harry: "Due to my own inability to cope with the world, I cannot find solutions. It’s as if the language was built incorrectly for discussing the subjects I really want to discuss."

Out of reach and wrapped in plastic on a top shelf was the Uher tape recorder that Harry had used for so many of his field recordings. Reel-to-reel tapes, carefully labeled, were also stacked on the top shelves, with the more important ones stored in the dresser drawers. If he was editing a Folkways record or movie soundtrack, he would always remove the tape from the recorder whenever he left the room, so if thieves stole the recorder they would not also get the tape. The dresser drawers contained a museum-quality collection of Seminole garments, which he once displayed for me, carefully unwrapping each folded piece from its tissue. Sitting on top of the bureau was every book by Frances Yates, and about fifty decks of tarot cards (Italian Renaissance, Romanian Gypsy, The Golden Dawn, and so on) including an original deck that Harry himself had designed (I wonder what became of that?). There was also a collection of Ukrainian hand-painted Easter eggs, stacks of string figures mounted on black cardboard, and the remnants of a collection of paper airplanes that Harry began picking up off the streets in the 1950s, when skyscraper windows could still be opened and bored office workers would sail gliders through the canyons of New York. Down through the years I often thought of Harry’s rooms as living beings, and I think he did, too. Every time he would leave, just as he was about to close the door and lock it, he’d peek back in and say, "Goodbye, room."

If Harry ever found a random note on the street, or especially a deranged screed posted to a lamppost, he would preserve it. He had a sense of historicity in the moment. Harry’s best friend at the Chelsea, Peggy Biderman, had a collection of letters from their mutual friend Jesse Turner—a young hustler and bank robber serving time in prison; Harry was adamant she should donate these to the Smithsonian. During Smith’s lifetime (and after), many of his collections found their way into the Smithsonian. The irony of the name of that institution was not lost on Harry.

The Chelsea lobby and rooftop were both hangouts for hotel residents, who were basically a bunch of bad children. Once, when the gaggle of residents socializing in the lobby numbered fifteen or twenty, the manager Stanley Bard emerged from his office, took in the scene with exasperation, and clapped his hands: "I want you all to go to your rooms!"—and everyone dispersed. The Chelsea rooftop was a communal space for all the residents until the early 1980s, when a few of the wealthy residents with penthouse apartments carved it up for their private use, with tacit permission from management. Harry filmed parts of Mahagonny up there, as well as the kaleidoscopic footage of Wendy Clarke doing the Boogaloo in a Rudi Gernreich dress. The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane both played impromptu concerts on the roof. One afternoon Leonard Cohen was waiting in the lobby for his mother to arrive from the airport—he was putting her up at the hotel for a week. When she arrived Leonard proudly introduced her to Harry. "Oh, Mrs. Cohen, you have a lovely son," he whined, "but he has a horrible voice." Leonard loved this.

Product Details

- Publisher: Park Street Press (July 8, 2025)

- Length: 384 pages

- ISBN13: 9798888501375

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Alchemist, magician, filmmaker, artist, mystic, anthropologist, collector, rebel, eternal omnivore, and 20th-century Renaissance man, Harry Smith was many things to many people, and this outstanding collection of lovingly written testimonies pays tribute to Harry with wit, respect, love, and laser-like precision. It is absolutely impossible to forget any interaction you had with Harry—and the beautiful tales in this remarkably readable and heartfelt book will have you awestruck, laughing out loud, and hungry for more. Perhaps the best collection of writings about one of the most enigmatic and fascinating figures the world has ever known.”

– John Zorn, American composer

“The Occult Harry Smith explores so many fascinating aspects of Harry Smith that have yet to be explored! Through a panoply of voices gathered in this volume, we get firsthand accounts and informed explorations that delve deep into the magician and trickster Harry Smith. Essential reading for anyone who wants to know more about this enigmatic and influential figure who lived his life on the edge and for his art.”

– Rani Singh, director of the Harry Smith Archives

“Through his alchemical metaphors and deep appreciation for cultural diversity, Smith’s work continues to influence new generations eager to learn more about his gentle blurring of the boundaries between art and magic. The Occult Harry Smith is a highly inspiring anthology and an invaluable glimpse into the timeless cosmic prism that was the mind of this polymath magus.”

– Carl Abrahamsson, author of Meetings with Remarkable Magicians and Occulture

“The world is blessed unknown when a Harry Smith enters it, and we are fortunate that enough individuals notice, to record his presence among them. One can only gain—and gain much—from reading this prismatic collection of fascinating views on the polymathic shaman of the city. Smith: all profit with no risk, other than the effect of enlightenment, a mere byproduct of gazing at his mighty works.”

– Tobias Churton, author of Aleister Crowley in England, Aleister Crowley in Paris, and Aleister Crowl

“This invaluable collection comes at the right time, as interest in Harry Smith’s life expands and his manifold work reaches new and ever-growing audiences. Offered up by the people who knew him best, this volume provides new and nuanced perspectives on Harry Smith: the man, the polymath, the sage.”

– John Klacsmann, archivist at Anthology Film Archives

“The Occult Harry Smith is a long overdue deep dive into this particular aspect of a wonderful, remarkable, and insufferable genius and polymath. In addition, by bringing together the memories and observations of an impressive, indeed close-to-definitive, collection of acolytes, scholars, and friends (not to mention photographic treasures and unpublished texts), Peter Valente presents an unexpected delight in this wide-ranging compendium—endlessly illuminating (as was Harry)—a posthumous banquet.”

– Simon Pettet, poet and author of Hearth, As A Bee, and More Winnowed Fragments

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Occult Harry Smith Trade Paperback 9798888501375